Tsz Kong Political Sim: Difference between revisions

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The Tsz Kong (Chinese: 紫港) Political Sim is an alternate-history political simulation. It is an auxiliary server of 852 Resurgence, and the spiritual successor of the East Macau Political Sim. The server went live on January 1, 2022, shortly after midnight. | The Tsz Kong (Chinese: 紫港) Political Sim is an alternate-history political simulation. It is an auxiliary server of 852 Resurgence, and the spiritual successor of the East Macau Political Sim. The server went live on January 1, 2022, shortly after midnight, and was run until January 4th 2024. | ||

==Simulation History == | ==Simulation History == | ||

The sim was hosted by Card0 from January until April, in its first 2 months of operation, the server was quite popular with talks of there even being a city building server hosted by Friedchilli. Throughout this time, Lieutenant Quattro served as the President of Tsz Kong, of the Zeonist Party. However as March came around, inactivity soared and members became apathetic to the server. | The sim was hosted by [[Card0]] from January until April, in its first 2 months of operation, the server was quite popular with talks of there even being a city building server hosted by [[Friedchilli]]. Throughout this time, [[Lieutenant Quattro]] served as the President of Tsz Kong, of the Zeonist Party. However as March came around, inactivity soared and members became apathetic to the server. Eventually, Card0 would transfer full ownership to [[flutters]] on April 15th 2022, hoping they could handle it while Card0 focused on other things. Unfortunately, inactivity remained high and the sim was suspended on April 25th 2022, though it has remained open to this day. | ||

On July 4th, the server would be revived as Card0 returned to managing the server. However, flutters would remain the owner. 6 days later, the first Tsz Kong Elections following the revival of the sim were held, [[RandomAutobiographyRoamer]] was elected as his party: the Nationalists won the election. However, he would be ousted via a vote of no confidence on July 13th due to the actions of some of his MPs. Elections were rescheduled for July 16th. He would later be accused of vote rigging and later was banned from both Tsz Kong and 852R as a whole. What followed was a period of activity but also drama as president [[Kevinovich]] through both of his nonconsecutive terms, tried to gain more and more control in the sim, leading Card0 to eventually try and prevent him in his second term. However, this left the sim growing more inactive. | |||

On | On January 17th 2023, Card0 made an emergency announcement in 852R urging members to join TK, calling it the "black sheep of hkgag". This led to a short period of increased activity before activity once again dropped. Following this, in March, Card0 also held a referendum on server reform, eventually leading to the server to be more "lore-focused" and having elections held every 3 months. | ||

After a long back and forth argument between April 1st and 2nd, [[Zy]] would be disposed as President on April 2nd 2023 due to his passive aggressiveness. RandomAutobiographyRoamer, who was unbanned from participating in politics, was re-elected Under his's leadership, many changes would made to the sim to boost activity such as new bots, reviving the judiciary and connecting to different political sims. However, despite the changes his 2-term administration made, his party would lose the next election, partially due to the fact that they took a long time in finding a suitable candidate. | |||

On January 4th 2024, due to low activity, the server was archived and the sim shut down. | |||

On January | |||

== Roles == | == Roles == | ||

| Line 28: | Line 22: | ||

===Prehistoric Era=== | ===Prehistoric Era=== | ||

===Imperial Era (221 BC-1828 AD) === | ===Imperial Era (221 BC-1828 AD) === | ||

During the Han Dynasty, a small military outpost was constructed at Shek Kwu Shan, | During the Han Dynasty, a small military outpost was constructed at Shek Kwu Shan. The outpost served as a strategic lookout for Han forces, but as the Jin Dynasty crumbled, the site was abandoned, left to the mercy of time and nature. Shek Kwu Shan was left uninhabited until centuries later, when during the Ming Dynasty, a small fishing village briefly flourished there, drawing settlers seeking refuge from the chaos of the mainland. Yet, like many coastal settlements of the era, it was short-lived, fading into obscurity once more. | ||

Another settlement: Lok Sha, rose to prominence as a bustling port town during the Tang Dynasty, its natural harbor attracting merchants from across the South China Sea. For a time, it thrived as a key trading hub, its markets filled with silks, spices, and ceramics. However, as dynasties shifted and trade routes changed, Lok Sha’s fortunes waned. By the Song Dynasty, the once-prosperous port had fallen into decline, its docks increasingly frequented by pirates who used the abandoned warehouses as hideouts. The Yuan Dynasty saw the town deserted entirely, until Ming-era migrants—fleeing unrest further north—revived it as a quiet fishing village, unaware of the colonial ambitions that would soon reshape their home. | |||

Everything changed in 1648, when the Dutch East India Company, eager to expand its Asian trade network, purchased Tsz Kong from the embattled Southern Ming regime. Desperate for European firearms to resist the advancing Qing forces, the Ming warlords reluctantly surrendered the territory. The Dutch quickly built Fort De Koong on the site of present-day Sham Uk, a sturdy bastion overlooking the sea, alongside a bustling trading post. For a brief time, Tsz Kong became a vital node in the Dutch spice trade—until the infamous Zheng Chenggong, better known as Koxinga, seized the fort in his campaign against the Qing. | |||

De Koong | The Dutch weren’t the only Europeans with eyes on Tsz Kong. In 1665, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, British forces stormed Fort De Koong, hoping to claim the lucrative outpost for themselves. Though they succeeded in capturing it, the Treaty of Breda in 1667 returned the territory to the Dutch—much to the frustration of British merchants. Over the next century, Tsz Kong remained a minor but profitable Dutch holding, its mixed population of Cantonese fishermen, Dutch traders, and Malay laborers creating a unique cultural blend. Mirroring their policies in Taiwan, the Dutch attempted to turn Tsz Kong into an agricultural export colony. They introduced sugarcane plantations, relying on imported laborers from Fujian and Guangdong, as well as enslaved people from Southeast Asia and Africa. Unlike in Taiwan, where the Dutch successfully exported deerskins and rice, Tsz Kong’s rugged terrain limited large-scale farming. Instead, the colony became a secondary hub for silk, porcelain, and smuggled goods—often bypassing Qing trade restrictions. The Dutch also encouraged Chinese merchants to settle in Tsz Kong, offering tax incentives, much like they had done in Anping in Taiwan. However, the colony never reached the same level of prosperity as Taiwan, remaining a minor outpost in the VOC’s vast network. But without the lucrative trade of Taiwan and facing constant threats from pirates, Qing forces, and rival Europeans, the Dutch reduced their presence. By the mid18th century, Tsz Kong was little more than a lightly garrisoned waystation for Dutch ships traveling between Batavia and Japan. | ||

By the early 19th century, however, the Dutch Empire’s influence in Asia was waning, and the colony's days seemed to be doomed. The Qing, while embattered by the First Opium War, were not fully humiliated, meaning that there was a real chance that the Qing could demand the city back. But that changed in 1858, when France, eager to establish its own foothold in southern China—negotiated the transfer of Tsz Kong from the Dutch in exchange for concessions elsewhere. The French saw potential in the territory’s deep-water ports and envisioned it as a gateway to the riches of inland China. | |||

Wanting to expand their colonial holdings in China, France was able to purchase the rest of mainland Tsz Kong from China in 1898 for $3 million thanks to a greater participation in the coalition. | ===Early Colonial Period (1858-1918)=== | ||

Following the end of the Second Opium War, China ceded the territories of modern-day Southern peninsular Tsz Kong(south of avenue de la Boundarie passing from Davistown to Oi Yip) to France at the Convention of Peking. The first governor, Antoine Cordier, declared the administrative centre of the territory to be in the general vicinity of Centrale in the modern-day. Wanting to expand their colonial holdings in China, France was able to purchase the rest of mainland Tsz Kong from China in 1898 for $3 million thanks to a greater participation in the coalition. France expanded the agricultural and trading economy of the colony and used it as a training ground for the local armed forces, aiming to compete with British colony in the area. Under their administration, Tsam Au Airport (then known as Tsz Kong Airfield), the Racecourse Grandé-Jardin and many other iconic facilities were established, in the hopes of creating a modern French city in Asia, though many of the majority Chinese neighbourhoods in the city remained impoverished. | |||

In the treaty of Peking, the British gained sovereignty over Tsz Kong Island alongside the Kowloon Peninsula, in accordance to their claims in the Anglo-Dutch wars. They initially constructed their settlement on what they originally called New Plymouth, atop and around Dutch fortifications which had been used as government headquarters for quite an amount of time, on the site of today's Nam Kong, with most of the west coming under British control. Like the French, the British held some hostility towards their counterpart, though they maintained good relations and drew closer as WW1 approached. The British would also sponsor the construction of the Belsunce-Canton railway, negotiating with the French to operate the railway in exchange for a cut of the profits, with the railway today being a part of the intercity railway that goes into central Tsz Kong. | |||

===Interwar Period (1918-1941)=== | |||

Following the end of WW1, Anglo-French colonial agreements shifted. This included the merger of British and French Tsz Kong into one single British Tsz Kong colony under the treaty of Sèvres (becoming its only actual effect). Yet, both French and British officials would continue to serve in their former positions, with the government of the colony being led by two co-governors, selected by the foreign offices of both countries. Thus, Tsz Kong became an anomaly: a colony ruled by two co-governors, one appointed by the British Foreign Office, the other by the French Ministry of Colonies. While this arrangement avoided outright conflict, it also led to bureaucratic paralysis, as the two governors frequently clashed over policy, budgets, and jurisdiction. | |||

While mainland China descended into fragmentation during the Warlord Era, Tsz Kong, much like nearby Hong Kong, became a rare enclave of stability. Its dual colonial status ironically made it a neutral ground for political exiles, merchants, and refugees fleeing the chaos. Both the KMT and the CCP sought to establish influence in the city, though British and French authorities carefully suppressed overt political agitation. The colony’s European quarters saw discreet meetings between Chinese revolutionaries and foreign sympathizers—most notably, a small contingent of French communists who traveled to Tsz Kong in the early 1920s to liaise with CCP members. However, their impact was minimal; the British governor, wary of Bolshevik influence, swiftly deported several French radicals, souring relations with Paris. | |||

In the | The Canton-Hong Kong Strike of 1925, a massive worker-led protest against British imperialism, sent ripples into Tsz Kong. While the colony was not a primary target, Chinese dockworkers and rickshaw pullers organized sympathy strikes, briefly paralyzing the port. Unlike in Hong Kong, where protests were met with brutal suppression, Tsz Kong’s dual administration created confusion—British police advocated for harsh crackdowns, while French officials, wary of escalating tensions, hesitated. In the end, the strikes were crushed within weeks, but the incident exposed the fragility of the condominium’s authority. To prevent future unrest, the colonial government imposed stricter controls on labor unions, pushing dissent underground. | ||

The interwar period saw Tsz Kong’s urban core expand dramatically. New neighborhoods sprang up, blending French colonial villas, British-style row houses, and Cantonese tenements, creating a uniquely hybrid architectural landscape. However, beyond the capital, the colony remained vastly underdeveloped. Most of Tsz Kong’s interior was dotted with sleepy market towns, where farmers and fishermen lived much as they had for centuries. The British focused on modernizing the port and military infrastructure, while the French invested in Catholic missions and rubber plantations—neither power saw much value in developing rural Tsz Kong. This neglect would later fuel resentment among the local population, who saw the benefits of colonialism flow only to a privileged few. | |||

With its lax oversight and divided administration, Tsz Kong became a hub for smuggling during the 1920s and 1930s. Opium, firearms, and luxury goods flowed through its poorly monitored docks, often with the tacit approval of corrupt officials. The French side, in particular, gained a reputation for turning a blind eye to arms shipments destined for warlords in Guangdong and Guangxi. Meanwhile, British customs officers focused on intercepting contraband heading into Hong Kong, creating a bizarre cat-and-mouse game between the two colonial factions. This illicit trade enriched a small class of comprador merchants, who operated with near-impunity, further entrenching Tsz Kong’s reputation as a "city of shadows." | |||

By the late 1930s, as Japan’s invasion of China intensified, Tsz Kong’s strategic position made it a potential target. The Anglo-French condominium, already strained by internal disputes, now faced an existential threat. British military planners quietly fortified the colony’s defenses, while the French—distracted by the looming war in Europe—did little to prepare. The local Chinese population, caught between colonial neglect and Japanese aggression, grew increasingly restless. Some began secretly aiding the KMT’s resistance efforts, while others saw the CCP as the only viable alternative to foreign rule. Regardless, a war was coming, and Tsz Kong would absolutely not be spared. | |||

===Japanese Occupation (1941-1945) === | ===Japanese Occupation (1941-1945) === | ||

On December 8th 1941, Tsz Kong was invaded by Japanese forces. Allied forces, consisting of British, French, American, Canadian, Australian and Indian troops defended the city fiercely but it would fall on February 12th 1942, just 3 days before Singapore would fall as well. Having surrendered to the Japanese, all the remaining forces were either imprisoned or executed. | On December 8th 1941, Tsz Kong was invaded by Japanese forces. Allied forces, consisting of British, French, American, Canadian, Australian and Indian troops defended the city fiercely but it would fall on February 12th 1942, just 3 days before Singapore would fall as well. Having surrendered to the Japanese, all the remaining forces were either imprisoned or executed. | ||

During this time, Tsz Kong suffered greatly, with food being fiercely rationed and the general quality of life dropping. It is estimated that over 530,000 people either died or escaped. A few of those people who escaped would later return as part of the East River (Dongjiang) Column, fighting in the countryside areas of Tsz Kong. | During this time, Tsz Kong suffered greatly, with food being fiercely rationed and the general quality of life dropping. It is estimated that over 530,000 people either died or escaped. A few of those people who escaped would later return as part of the East River (Dongjiang) Column, fighting in the countryside areas of Tsz Kong, much like Hong Kong. The Dongjiang Column would also assist in helping Chinese elites, based in Tsz Kong to escape to nationalist-communist controlled territory. | ||

The territory was handed over back to joint British-French control on August 30th 1945, the same day Hong Kong would be liberated as well. That day, known as Liberation Day, is still celebrated in | The territory was handed over back to joint British-French control on August 30th 1945, the same day Hong Kong would be liberated as well. That day, known as Liberation Day, is still celebrated in Tsz Kong to this day and is a public holiday. | ||

=== Post-War Colonial Era (1945-1971)=== | === Post-War Colonial Era (1945-1971)=== | ||

In the aftermath of WW2, it was unknown who would control Tsz Kong in the long term. While the Republic of China, under Chiang Kaishek, wanted to gain back all European concessions, including Tsz Kong, the UK and France protested this, arguing that they had been the first to liberate the territory. The US had initially argued in favour of restoring Chinese rule over Tsz Kong, however with the resumption of the Chinese Civil War in 1946, it withdrew its calls for returning Tsz Kong. During this time, pro-autonomy sentiments grew among Tsz Kongers, especially those who had been educated overseas pre-war. While the UK and France would end many of its discriminatory laws, these sentiments would persist. | In the aftermath of WW2, it was unknown who would control Tsz Kong in the long term. While the Republic of China, under Chiang Kaishek, wanted to gain back all European concessions, including Tsz Kong, the UK and France protested this, arguing that they had been the first to liberate the territory and therefore, had the best claim to Tsz Kong. The US had initially argued in favour of restoring Chinese rule over Tsz Kong, however with the resumption of the Chinese Civil War in 1946, it withdrew its calls for returning Tsz Kong due to the instability. During this time, pro-autonomy sentiments grew among Tsz Kongers, especially those who had been educated overseas pre-war, with some even beginning to call for outright independence if their needs could not be met. While the UK and France would end many of its discriminatory laws in the colony, these sentiments would persist until the end of the colonial period. | ||

Tsz Kong would boom as an industrial hub in the 1950s, with the population growing as a result of refugees escaping to the city after the civil war. Most of the refugees were either Cantonese (specifically Chiuchow) and Fujianese, though there were some Shanghainese and Zhejiangnese who came during this time. Many of these, being intellectuals, would find Tsz Kong to be a preferable home to the mainland, and dreamt of making a free republic. This led the pro-autonomy movement to grow into a full-fledged independence movement by the 1960s, with protests being held regularly demanding it. Initially though, the UK and France were concerned that this would anger China, while also inspiring their remaining colonies to fight for independence. As a result, they tried to suppress this but ultimately failed with American condemnation. They then satisfy the moderates, by allowing for the Legislative Council to | Tsz Kong would boom as an industrial hub in the 1950s, with the population growing as a result of refugees escaping to the city after the civil war. Most of the refugees were either Cantonese (specifically Chiuchow) and Fujianese, though there were some Shanghainese and Zhejiangnese who came during this time. Many of these, being intellectuals, would find Tsz Kong to be a preferable home to the mainland, and dreamt of making a free republic. This led the pro-autonomy movement to grow into a full-fledged independence movement by the 1960s, with protests being held regularly demanding it. Initially though, the UK and France were concerned that this would anger China, while also inspiring their remaining colonies to fight for independence. As a result, they tried to suppress this but ultimately failed with American condemnation. They then satisfy the moderates, by allowing for the Legislative Council to become a democratically elected legislature in 1965, though this only emboldened the movement. Many of the existing political parties, who acted more as social organizations rather than proper parties before 1965, would run candidates for the election. | ||

Secretly, the US made a deal with the UK and France in 1966, they could let Tsz Kong go but still have a great deal of influence over it. The UK would accept this, though France was more reluctant and would only accept this 3 years later in 1969. Around the same time, Hong Kong also was inspired by Tsz Kong's independence movement as an independence movement also starting growing there. | Secretly, the US made a deal with the UK and France in 1966, they could let Tsz Kong go but still have a great deal of influence over it. The UK would accept this, though France was more reluctant and would only accept this 3 years later in 1969. Around the same time, Hong Kong also was inspired by Tsz Kong's independence movement as an independence movement also starting growing there. 4 main parties emerged in Tsz Kong during this time: the Democratic Party: the moderate faction of the pro-independence movement, the Ji Yau Dong: the radical faction of the pro-independence movement, the Workers Party: a socialist party secretly backed by the CCP, and the Labor Party: an independent left-wing party. | ||

Unlike | Unlike OTL, Henry Kissinger would make his secret trip to China a year earlier in 1970, which would lay the groundwork to better US relations with China. Kissinger persuaded China to give up claims on Hong Kong and Tsz Kong, but that it could get Macau back eventually. Surprisingly, the Chinese authorities agreed to this, and later made a public statement claiming that they would not invade an independent Hong Kong and Tsz Kong should that happen. The same year in May, a referendum was held: to go independent, to stay a colony, or to rejoin China. 63.8% of voters voted for independence as a republic. As a part of the deal, British and French forces would remain in Tsz Kong primarily to help train the new Tsz Kong army, but they would withdraw most of their forces to avoid antagonising China. A constitutional convention was called later that year, involving all the major political figures in the city, to draft a constitution for the republic. While some pushed for a parliamentary republic, with the President being a ceremonial head of state, most pushed for a presidential republic instead, though the parliament was given more powers. | ||

===Independence Era (1971-Present Day)=== | ===Independence Era (1971-Present Day)=== | ||

On May | On May 12, 1971, after decades of colonial rule and postwar political maneuvering, Tsz Kong finally gained independence as a sovereign republic. The transition was neither smooth nor entirely peaceful—years of negotiations with Britain and France had been fraught with disputes over military bases, economic concessions, and the rights of European settlers. The country’s first president, Clark Man Tsz Cheung, a charismatic lawyer and leader of the Democratic Party (Min Zhu Dang), took office amidst both celebration and tension. His party had formed an uneasy alliance with the Ji Yau Dong (Freedom Movement), a nationalist group that had long agitated for independence. Together, they narrowly secured power against a fractured opposition that now included the Tong Heung Kuk (United Welfare Association), a conservative, business-aligned faction that had unexpectedly won seats in the first post-independence elections. Though not a traditional political party, the Tong Heung Kuk represented the old elite—colonial-era compradors, industrialists, and even former collaborators with the Japanese occupation—who now sought to maintain influence in the new republic. | ||

The first decade of independence tested Tsz Kong’s fragile democracy. President Man's government faced labor strikes, student protests, and accusations of corruption, while the Tong Heung Kuk used its economic power to undermine reforms. Meanwhile, the Ji Yau Dong, once a key ally, grew disillusioned with the Democratic Party’s compromises and began pushing for more radical land redistribution and anti-colonial rhetoric. The Nationalist Party also rose around this time, arguing for firm anti-communist rhetoric, while also pushing for more autocratic policies. By the mid-1970s, the republic was at a crossroads—would it become a Western-aligned capitalist state like Singapore, or would it embrace more revolutionary rhetoric, aligning itself with China? The answer came through an unexpected force: economic necessity. With few natural resources and a small domestic market, Tsz Kong had no choice but to embrace export-led growth, following the model of its neighbors. | |||

By the late 1970s, Tsz Kong had transformed into one of the "Five Asian Tigers", alongside Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Its economy boomed thanks to light manufacturing, electronics, and a bustling port sector, while its unique Franco-Cantonese culture became a selling point for tourism. The government invested heavily in education, creating a skilled workforce that attracted foreign investment. Culturally, the 1980s were a golden age—Tsz Kong’s film industry, known for its stylish crime thrillers and romantic melodramas, gained international acclaim, while its Mandopop and Cantopop stars rivalled those of Hong Kong and Taiwan. The capital, Victoria-Sham Uk, became a glittering metropolis of neon-lit streets, French-inspired cafés, and bustling night markets. | |||

With the fall of the communist regime in China in 1989 (which marks the main POD of this timeline aside from Tsz Kong's existence), relations would improve with both Tsz Kong and China, as well as the newly independent Hong Kong which gained its independence in 1995. However, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis hit Tsz Kong hard. As investors fled emerging markets, the republic’s currency plummeted, and property prices collapsed. Unemployment soared, and for the first time in two decades, the economy shrank. The government’s response—a mix of austerity measures and IMF-backed reforms—sparked public outrage. The Tong Heung Kuk, now rebranded as the New Prosperity Alliance, blamed the Democratic Party for mismanagement, while leftist groups accused the elite of protecting their wealth at the expense of the poor. The crisis marked the end of Tsz Kong’s unbridled optimism, forcing a national reckoning with its economic model. | |||

Though the golden age had passed, Tsz Kong’s cultural influence endured. Its films and music remained popular across Asia, and its hybrid Franco-Cantonese identity became a point of national pride. Politically, however, the republic entered a new era of volatility—one where the promises of democracy, prosperity, and equality would be fiercely contested in the decades to come. | |||

Today, Tsz Kong faces a complex array of challenges that test its political stability, economic resilience, and social cohesion. One of the most pressing issues is rising inequality, as the wealth gap between the urban elite and the working class continues to widen, exacerbated by skyrocketing housing prices and stagnating wages. The legacy of its rapid industrialization has also left the country grappling with environmental degradation, including conerns around air pollution and contamination of coastal waters from decades of unregulated manufacturing. | |||

Externally, Tsz Kong faces geopolitical pressures, particularly from China’s increasing regional influence, which has led to tensions over trade, investment, and fears of losing autonomy. Finally, the aging population and declining birthrate threaten long-term economic sustainability, forcing difficult debates over immigration policy and pension reforms. Together, these issues paint a picture of a nation at a crossroads, balancing its storied past with an uncertain future. | |||

==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

Upon inspection, Tsz Kong appears similar to the Special Administrative Regions | Upon inspection, Tsz Kong appears similar to the Special Administrative Regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau, also located in Southern China. However, Tsz Kong is an independent city-state, more akin to Singapore. Most of the city is located on a peninsula, though there are sveral significant outlying islands. | ||

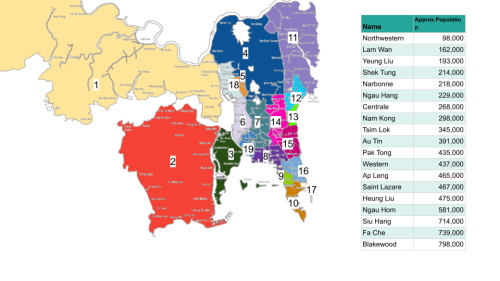

[[File:Tkmap.png|thumb|500x500px|Map of Tsz Kong and notable places]] | |||

[[File:Tkdistrictmap.png|thumb|500x500px|Map of Districts]] | |||

=== Districts === | |||

The city was reorganised into several districts after independence, replacing the old informal neighbourhoods that had existed since the colonial period, while also formally dividing the different regions which had been used for elections. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+ | |||

| | |||

|'''Name''' | |||

|'''Approx.Population''' | |||

|'''District Council Seats''' | |||

|- | |||

|1 | |||

|Northwestern | |||

|98,000 | |||

|15 | |||

|- | |||

|2 | |||

|Lam Wan | |||

|162,000 | |||

|13 | |||

|- | |||

|3 | |||

|Yeung Liu | |||

|193,000 | |||

|17 | |||

|- | |||

|4 | |||

|Shek Tung | |||

|214,000 | |||

|15 | |||

|- | |||

|5 | |||

|Narbonne | |||

|218,000 | |||

|21 | |||

|- | |||

|6 | |||

|Ngau Hang | |||

|229,000 | |||

|14 | |||

|- | |||

|7 | |||

|Centrale | |||

|268,000 | |||

|14 | |||

|- | |||

|8 | |||

|Nam Kong | |||

|298,000 | |||

|12 | |||

|- | |||

|9 | |||

|Tsim Lok | |||

|345,000 | |||

|22 | |||

|- | |||

|10 | |||

|Au Tin | |||

|391,000 | |||

|19 | |||

|- | |||

|11 | |||

|Pak Tong | |||

|435,000 | |||

|16 | |||

|- | |||

|12 | |||

|Western | |||

|437,000 | |||

|24 | |||

|- | |||

|13 | |||

|Ap Leng | |||

|465,000 | |||

|16 | |||

|- | |||

|14 | |||

|Saint Lazare | |||

|467,000 | |||

|21 | |||

|- | |||

|15 | |||

|Heung Liu | |||

|475,000 | |||

|19 | |||

|- | |||

|16 | |||

|Ngau Hom | |||

|581,000 | |||

|32 | |||

|- | |||

|17 | |||

|Siu Hang | |||

|714,000 | |||

|33 | |||

|- | |||

|18 | |||

|Fa Che | |||

|739,000 | |||

|36 | |||

|- | |||

|19 | |||

|Blakewood | |||

|798,000 | |||

|38 | |||

|} | |||

==Government== | ==Government== | ||

A Parliament and a President are chosen through elections every 3 months. | A Parliament and a President are chosen through elections every 3 months. | ||

| Line 90: | Line 207: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|2 | |2 | ||

|[[ | |[[RandomAutobiographyRoamer]] | ||

|[[Tsz Kong Nationalist Party]] | |[[Tsz Kong Nationalist Party|Nationalist Party]] | ||

|July 10th 2022-July 16th 2022 (ousted by no confidence vote and emergency election) | |July 10th 2022-July 16th 2022 (ousted by no confidence vote and emergency election) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 106: | Line 223: | ||

|5 | |5 | ||

|[[Citric Acid]] | |[[Citric Acid]] | ||

|[[Tsz Kong Greens]] | |[[Tsz Kong Greens|Greens]] | ||

|September 8th 2022-October 8th 2022 | |September 8th 2022-October 8th 2022 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 125: | Line 242: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|9 | |9 | ||

|Zy | |[[Zy]] | ||

|[[Socialist Party of Pixzy]] | |[[Socialist Party of Pixzy]] | ||

|March 19th 2023-April 2nd 2023 (deposed by God) | |March 19th 2023-April 2nd 2023 (deposed by God) | ||

|- | |- | ||

|10 | |10 | ||

|[[ | |[[RandomAutobiographyRoamer]] | ||

|[[Reformist Nationalist Party]] | |[[Reformist Nationalist Party]] | ||

| April 4th 2023-October 8th 2023 | | April 4th 2023-October 8th 2023 | ||

| Line 137: | Line 254: | ||

|[[Lieutenant Quattro]] | |[[Lieutenant Quattro]] | ||

|[[Marxist Leninist Maoist Party]] | |[[Marxist Leninist Maoist Party]] | ||

|October 8th 2023- | |October 8th 2023-January 4th 2024 | ||

|} | |} | ||

===Current Parties=== | ===Current Parties=== | ||

| Line 144: | Line 261: | ||

!Party Name (Traditional Chinese/French) | !Party Name (Traditional Chinese/French) | ||

!Party Beliefs | !Party Beliefs | ||

!Foundation Date (Lore) | |||

!Party Leader | !Party Leader | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 150: | Line 268: | ||

民主社會聯盟 | 民主社會聯盟 | ||

|Democratic Socialism, Pro-democracy, Anti Authoritarianism, and Semi-Presidentialism | |Democratic Socialism, Pro-democracy, Anti Authoritarianism, and Semi-Presidentialism | ||

|2023, | |||

Democratic Socialist Alliance(1978), | |||

The Greens (1995) | |||

|[[Aqua]] | |[[Aqua]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 156: | Line 277: | ||

新國民黨 | 新國民黨 | ||

|Nationalism, State capitalism, Anti-authoritarian communism, Militarism, Right-wing populism, Social conservatism, technocracy | |Nationalism, State capitalism, Anti-authoritarian communism, Militarism, Right-wing populism, Social conservatism, technocracy | ||

|[[ | |1996 | ||

|[[RandomAutobiographyRoamer]] | |||

|- | |- | ||

|[[League of Tsz Kong Unity]] | |[[League of Tsz Kong Unity]] | ||

| Line 162: | Line 284: | ||

紫港團結聯盟 | 紫港團結聯盟 | ||

|Centre-Right | |Centre-Right | ||

|1971 | |||

|[[Sid]] | |[[Sid]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 168: | Line 291: | ||

馬主義政黨 | 馬主義政黨 | ||

|People's Democracy | |People's Democracy | ||

|1966 (as Workers Party) | |||

|[[Lieutenant Quattro]] | |[[Lieutenant Quattro]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 174: | Line 298: | ||

同性戀黨 | 同性戀黨 | ||

|Single-Issue Politics, Pro LGBT, Anti Discrimination | |Single-Issue Politics, Pro LGBT, Anti Discrimination | ||

|2021 | |||

|[[Keq]] | |[[Keq]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 180: | Line 305: | ||

候補黨 | 候補黨 | ||

|Conservativism, Populism, Nationalism, Anti-Socialist/Communist, Integrationism | |Conservativism, Populism, Nationalism, Anti-Socialist/Communist, Integrationism | ||

|2006 | |||

|[[Dusk]] | |[[Dusk]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 186: | Line 312: | ||

團結黨 | 團結黨 | ||

|Pro-choice, anti-socialist, pro-secular, center-right, Pro-trade tariffs | |Pro-choice, anti-socialist, pro-secular, center-right, Pro-trade tariffs | ||

|1982 | |||

|[[Ky3653]] | |[[Ky3653]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 192: | Line 319: | ||

正公黨 | 正公黨 | ||

|Mainly focuses on promoting policies that are grounded in the principles of justice, public safety, and civil liberties. | |Mainly focuses on promoting policies that are grounded in the principles of justice, public safety, and civil liberties. | ||

|1975 | |||

|[[LazerTC]] | |[[LazerTC]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 198: | Line 326: | ||

新民主盟 | 新民主盟 | ||

|Centre-Left | |Centre-Left | ||

|1992 (as NDC), 1965 (as Democratic Party) | |||

|[[Freamy Icy Creamy]] | |[[Freamy Icy Creamy]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 204: | Line 333: | ||

粵區聯邦黨 | 粵區聯邦黨 | ||

|Guangdong-Tsz Kong unity, Cantonese patriotism, interventionism, anti-fascism, anti-communism, federalism, social liberalism | |Guangdong-Tsz Kong unity, Cantonese patriotism, interventionism, anti-fascism, anti-communism, federalism, social liberalism | ||

|2014 | |||

|[[Tiandianp]] | |[[Tiandianp]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 210: | Line 340: | ||

自由黨 | 自由黨 | ||

|Free Market, Centrist Lib-Left, Pro LGBT | |Free Market, Centrist Lib-Left, Pro LGBT | ||

|1964 | |||

|[[Idiotroaster]] | |[[Idiotroaster]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 216: | Line 347: | ||

卡迪黨 | 卡迪黨 | ||

|Anti-Authoritarianism, Anti-Capitalism, Anarchism | |Anti-Authoritarianism, Anti-Capitalism, Anarchism | ||

|2022 | |||

|[[Stormin]] | |[[Stormin]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Tsz Kong Democratic Party]] | |[[Tsz Kong Democratic Party]]* | ||

|Parti démocratique | |Parti démocratique | ||

民主黨 | 民主黨 | ||

|Nationalism, Conservatism | |Nationalism, Conservatism | ||

|1996 | |||

|[[Bricky]] | |[[Bricky]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 228: | Line 361: | ||

自右黨 | 自右黨 | ||

|Social Libertarianism, Free Market Economy, Low Taxes | |Social Libertarianism, Free Market Economy, Low Taxes | ||

|2001 | |||

|[[kingsnake1]] | |[[kingsnake1]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 234: | Line 368: | ||

yuu黨 | yuu黨 | ||

|Authoritarianism, economically right/free markets, capitalist, promotes shopping and advertisement/product development | |Authoritarianism, economically right/free markets, capitalist, promotes shopping and advertisement/product development | ||

|2016 | |||

|[[Greentea]] | |[[Greentea]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 240: | Line 375: | ||

海洋黨 | 海洋黨 | ||

|Libertarian, small businesses, cultural preservation, progressive politics | |Libertarian, small businesses, cultural preservation, progressive politics | ||

|1999 | |||

|[[Yosh]] | |[[Yosh]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 246: | Line 382: | ||

青年黨 | 青年黨 | ||

|Social Welfare, Social Democracy, Anti-Communism, Anti-Fascism, Third-Way | |Social Welfare, Social Democracy, Anti-Communism, Anti-Fascism, Third-Way | ||

|2008 | |||

|[[Fork]] | |[[Fork]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 252: | Line 389: | ||

草地黨 | 草地黨 | ||

|Socialism, Anti-Authoritarianism, Anti-Capitalism | |Socialism, Anti-Authoritarianism, Anti-Capitalism | ||

|2016 | |||

|[[June]] | |[[June]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 258: | Line 396: | ||

紫港共產黨 | 紫港共產黨 | ||

|Tsz Kongian Socialism, Communism, Marxism-Leninism, Tsz Kong National Liberation, Peasant-Worker Solidarity, Left- Wing Populism, Pan Socialist Unity, Anti-fascism, Anti-racism. | |Tsz Kongian Socialism, Communism, Marxism-Leninism, Tsz Kong National Liberation, Peasant-Worker Solidarity, Left- Wing Populism, Pan Socialist Unity, Anti-fascism, Anti-racism. | ||

|1974 | |||

|[[rara_57]] | |[[rara_57]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

<nowiki>*</nowiki>Not to be confused the former Democratic Party created in 1966. | |||

===Former Parties=== | ===Former Parties=== | ||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| Line 270: | Line 411: | ||

|獎門黨/Parti Ruffiste | |獎門黨/Parti Ruffiste | ||

|[[Ruffism]] | |[[Ruffism]] | ||

|[ | |[[Aqua]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Tsz Kong Nationalist Party]] | |[[Tsz Kong Nationalist Party]] | ||

|紫港國民黨/Parti national de Tsz Kong | |紫港國民黨/Parti national de Tsz Kong | ||

|Nationalism,Anti communism, State capitalism, Anti-communist, Anti-Marxism, Anti-socialism, Militarism ,Right-wing populism, Social conservatism, technocracy | |Nationalism,Anti communism, State capitalism, Anti-communist, Anti-Marxism, Anti-socialism, Militarism ,Right-wing populism, Social conservatism, technocracy | ||

| | |[[RandomAutobiographyRoamer]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Social Democratic Worker's Party]] | |[[Social Democratic Worker's Party]] | ||

| Line 327: | Line 468: | ||

|Ronak | |Ronak | ||

|} | |} | ||

== Education == | |||

The named schools are listed below, taking in account population and education level (thus referencing Belgium) to around 3200+ schools<ref>https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/belgium-flemish-community/statistics-educational-institutions</ref> | |||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

!School Name | |||

!Associations | |||

!Principal | |||

!Aim | |||

!School Size | |||

!School Motto | |||

!School Transport | |||

!Education Level | |||

!Courses | |||

!Created by | |||

|- | |||

|[[Coastline Junior School]] | |||

| rowspan="5" |[[Tsz Kong International Schools Foundation]] (TKISF) | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|600 | |||

| | |||

| rowspan="5" |[[Joyful Bus|Joyful Bus 快樂巴士]] | |||

|Years 1-6 | |||

|Primary School | |||

| rowspan="5" |[[flutters]] | |||

|- | |||

|[[Hillside Junior School]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|600 | |||

| | |||

|Years 1-6 | |||

|Primary School | |||

|- | |||

|[[Turquoise Junior School]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|600 | |||

| | |||

|Years 1-6 | |||

|Primary School | |||

|- | |||

|[[Horizon School]] | |||

|Ms Joy WONG | |||

|To allow students to identify themselves freely and to find themselves. | |||

|1050 | |||

|Laetitiam Litterarum | |||

|Years 7-13 | |||

|MYP, iGCSE, A-Levels, BTEC | |||

|- | |||

|[[Tsz Kong International School]] | |||

|Ms Winnie POWELL | |||

| | |||

|1050 | |||

| | |||

|Years 7-13 | |||

|MYP, iGCSE, A-Levels | |||

|- | |||

|South Centrale Ruffist School | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|Education with ruffist beliefs | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|[[frogggggg]] | |||

|- | |||

|[https://hongkongggag.fandom.com/wiki/Springfield_International_School Springfield International School] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|To let pupils broaden their experiences through international connections | |||

|1400 | |||

| | |||

|Springfield International School buses | |||

|Years 1-13 | |||

|iGCSE, A-levels, | |||

international Baccalaureate | |||

| iancyh | |||

|- | |||

| Kalos | |||

Middle-High | |||

| | |||

|Mr Gary OAK | |||

|To provide free, quality trilingual education and to prepare teenagers to enter society | |||

|600 | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|Years 7-13 | |||

|iGCSE, A-levels, | |||

international Baccalaureate | |||

|[[Ash]] | |||

|} | |||

== Transport == | |||

Tsz Kong today has a developed public transportation network, consisting primarily of an intricate network of buses, and the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), which has been referred to as the city's backbone. | |||

Four main franchised bus companies operate in Tsz Kong: MetroBus, VitBu and TransCity, though several other companies operate shuttle bus services. | |||

The MRT, opening in 1981, operates 9 lines across the city, as well as a light rail system in the northwest and northeast, which are connected to MRT stations. Other independent railways like the Saisan Island Railway, also exist. | |||

Tsz Kong has one main airport: Tsz Kong Hung Long International Airport, also known simply as Tsz Kong International Airport, located in Lam Wan District. The airport is a major hub in Southern China, having several flights in and out of Asia. The airport is a hub to four airlines: Tsz Kong Airlines, Han Airlines, TKExpress and BuzzAir, all four of which are based in the city. The airport has 3 runways, and four terminals, and was opened in 1986 to replace the old airport located in Tsam Au Airport. | |||

''Link to Transit Information:'' https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1OjoGukFP9TFG-SsHggjIqU1Fk7NEZZ4t8feOqchLRRg/edit?usp=sharing | |||

''Link to Airline and Airport Informaiton:'' https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/10vWt-7IeQOg_DbenuJOxmUwQQsTF2w0s0Q2Mt1DZK2Y/edit?gid=385557387#gid=385557387 | |||

==Information and Resources == | ==Information and Resources == | ||

===Currency=== | ===Currency=== | ||

| Line 353: | Line 602: | ||

22 - China | 22 - China | ||

23 - Other regions | 23 - Other regions* | ||

<nowiki>*</nowiki>All vehicles that enter Tsz Kong must register for a Tsz Kong licence plate, that can be displayed alongside other licence plates. | |||

==== Reserved Prefixes (All are 3 digit codes) ==== | ==== Reserved Prefixes (All are 3 digit codes) ==== | ||

| Line 366: | Line 617: | ||

Vanity Plates must fall within 8 characters maximum (not including spaces, just as long as it can fit the standard size) and not use the characters I/O/Q. All has to be approved by the Tsz Kong Transport Department. It must be appropriate and not include any vulgar and offensive language. | Vanity Plates must fall within 8 characters maximum (not including spaces, just as long as it can fit the standard size) and not use the characters I/O/Q. All has to be approved by the Tsz Kong Transport Department. It must be appropriate and not include any vulgar and offensive language. | ||

* JE T | * JE T A1ME | ||

* CARD0 | * CARD0 | ||

* GAGGYDAD | * GAGGYDAD | ||

Latest revision as of 17:06, 18 August 2025

The Tsz Kong (Chinese: 紫港) Political Sim is an alternate-history political simulation. It is an auxiliary server of 852 Resurgence, and the spiritual successor of the East Macau Political Sim. The server went live on January 1, 2022, shortly after midnight, and was run until January 4th 2024.

Simulation History

The sim was hosted by Card0 from January until April, in its first 2 months of operation, the server was quite popular with talks of there even being a city building server hosted by Friedchilli. Throughout this time, Lieutenant Quattro served as the President of Tsz Kong, of the Zeonist Party. However as March came around, inactivity soared and members became apathetic to the server. Eventually, Card0 would transfer full ownership to flutters on April 15th 2022, hoping they could handle it while Card0 focused on other things. Unfortunately, inactivity remained high and the sim was suspended on April 25th 2022, though it has remained open to this day.

On July 4th, the server would be revived as Card0 returned to managing the server. However, flutters would remain the owner. 6 days later, the first Tsz Kong Elections following the revival of the sim were held, RandomAutobiographyRoamer was elected as his party: the Nationalists won the election. However, he would be ousted via a vote of no confidence on July 13th due to the actions of some of his MPs. Elections were rescheduled for July 16th. He would later be accused of vote rigging and later was banned from both Tsz Kong and 852R as a whole. What followed was a period of activity but also drama as president Kevinovich through both of his nonconsecutive terms, tried to gain more and more control in the sim, leading Card0 to eventually try and prevent him in his second term. However, this left the sim growing more inactive.

On January 17th 2023, Card0 made an emergency announcement in 852R urging members to join TK, calling it the "black sheep of hkgag". This led to a short period of increased activity before activity once again dropped. Following this, in March, Card0 also held a referendum on server reform, eventually leading to the server to be more "lore-focused" and having elections held every 3 months.

After a long back and forth argument between April 1st and 2nd, Zy would be disposed as President on April 2nd 2023 due to his passive aggressiveness. RandomAutobiographyRoamer, who was unbanned from participating in politics, was re-elected Under his's leadership, many changes would made to the sim to boost activity such as new bots, reviving the judiciary and connecting to different political sims. However, despite the changes his 2-term administration made, his party would lose the next election, partially due to the fact that they took a long time in finding a suitable candidate.

On January 4th 2024, due to low activity, the server was archived and the sim shut down.

Roles

God

God is a role held by admins to change lore, approve and give situations to Tsz Kong. At this moment, Card0 and flutters have this role.

Jesus

Jesus is a role, as a child of god, is the 2nd rank of administration, once held by flutters.

Lore (Unfinished)

Prehistoric Era

Imperial Era (221 BC-1828 AD)

During the Han Dynasty, a small military outpost was constructed at Shek Kwu Shan. The outpost served as a strategic lookout for Han forces, but as the Jin Dynasty crumbled, the site was abandoned, left to the mercy of time and nature. Shek Kwu Shan was left uninhabited until centuries later, when during the Ming Dynasty, a small fishing village briefly flourished there, drawing settlers seeking refuge from the chaos of the mainland. Yet, like many coastal settlements of the era, it was short-lived, fading into obscurity once more.

Another settlement: Lok Sha, rose to prominence as a bustling port town during the Tang Dynasty, its natural harbor attracting merchants from across the South China Sea. For a time, it thrived as a key trading hub, its markets filled with silks, spices, and ceramics. However, as dynasties shifted and trade routes changed, Lok Sha’s fortunes waned. By the Song Dynasty, the once-prosperous port had fallen into decline, its docks increasingly frequented by pirates who used the abandoned warehouses as hideouts. The Yuan Dynasty saw the town deserted entirely, until Ming-era migrants—fleeing unrest further north—revived it as a quiet fishing village, unaware of the colonial ambitions that would soon reshape their home.

Everything changed in 1648, when the Dutch East India Company, eager to expand its Asian trade network, purchased Tsz Kong from the embattled Southern Ming regime. Desperate for European firearms to resist the advancing Qing forces, the Ming warlords reluctantly surrendered the territory. The Dutch quickly built Fort De Koong on the site of present-day Sham Uk, a sturdy bastion overlooking the sea, alongside a bustling trading post. For a brief time, Tsz Kong became a vital node in the Dutch spice trade—until the infamous Zheng Chenggong, better known as Koxinga, seized the fort in his campaign against the Qing.

The Dutch weren’t the only Europeans with eyes on Tsz Kong. In 1665, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, British forces stormed Fort De Koong, hoping to claim the lucrative outpost for themselves. Though they succeeded in capturing it, the Treaty of Breda in 1667 returned the territory to the Dutch—much to the frustration of British merchants. Over the next century, Tsz Kong remained a minor but profitable Dutch holding, its mixed population of Cantonese fishermen, Dutch traders, and Malay laborers creating a unique cultural blend. Mirroring their policies in Taiwan, the Dutch attempted to turn Tsz Kong into an agricultural export colony. They introduced sugarcane plantations, relying on imported laborers from Fujian and Guangdong, as well as enslaved people from Southeast Asia and Africa. Unlike in Taiwan, where the Dutch successfully exported deerskins and rice, Tsz Kong’s rugged terrain limited large-scale farming. Instead, the colony became a secondary hub for silk, porcelain, and smuggled goods—often bypassing Qing trade restrictions. The Dutch also encouraged Chinese merchants to settle in Tsz Kong, offering tax incentives, much like they had done in Anping in Taiwan. However, the colony never reached the same level of prosperity as Taiwan, remaining a minor outpost in the VOC’s vast network. But without the lucrative trade of Taiwan and facing constant threats from pirates, Qing forces, and rival Europeans, the Dutch reduced their presence. By the mid18th century, Tsz Kong was little more than a lightly garrisoned waystation for Dutch ships traveling between Batavia and Japan.

By the early 19th century, however, the Dutch Empire’s influence in Asia was waning, and the colony's days seemed to be doomed. The Qing, while embattered by the First Opium War, were not fully humiliated, meaning that there was a real chance that the Qing could demand the city back. But that changed in 1858, when France, eager to establish its own foothold in southern China—negotiated the transfer of Tsz Kong from the Dutch in exchange for concessions elsewhere. The French saw potential in the territory’s deep-water ports and envisioned it as a gateway to the riches of inland China.

Early Colonial Period (1858-1918)

Following the end of the Second Opium War, China ceded the territories of modern-day Southern peninsular Tsz Kong(south of avenue de la Boundarie passing from Davistown to Oi Yip) to France at the Convention of Peking. The first governor, Antoine Cordier, declared the administrative centre of the territory to be in the general vicinity of Centrale in the modern-day. Wanting to expand their colonial holdings in China, France was able to purchase the rest of mainland Tsz Kong from China in 1898 for $3 million thanks to a greater participation in the coalition. France expanded the agricultural and trading economy of the colony and used it as a training ground for the local armed forces, aiming to compete with British colony in the area. Under their administration, Tsam Au Airport (then known as Tsz Kong Airfield), the Racecourse Grandé-Jardin and many other iconic facilities were established, in the hopes of creating a modern French city in Asia, though many of the majority Chinese neighbourhoods in the city remained impoverished.

In the treaty of Peking, the British gained sovereignty over Tsz Kong Island alongside the Kowloon Peninsula, in accordance to their claims in the Anglo-Dutch wars. They initially constructed their settlement on what they originally called New Plymouth, atop and around Dutch fortifications which had been used as government headquarters for quite an amount of time, on the site of today's Nam Kong, with most of the west coming under British control. Like the French, the British held some hostility towards their counterpart, though they maintained good relations and drew closer as WW1 approached. The British would also sponsor the construction of the Belsunce-Canton railway, negotiating with the French to operate the railway in exchange for a cut of the profits, with the railway today being a part of the intercity railway that goes into central Tsz Kong.

Interwar Period (1918-1941)

Following the end of WW1, Anglo-French colonial agreements shifted. This included the merger of British and French Tsz Kong into one single British Tsz Kong colony under the treaty of Sèvres (becoming its only actual effect). Yet, both French and British officials would continue to serve in their former positions, with the government of the colony being led by two co-governors, selected by the foreign offices of both countries. Thus, Tsz Kong became an anomaly: a colony ruled by two co-governors, one appointed by the British Foreign Office, the other by the French Ministry of Colonies. While this arrangement avoided outright conflict, it also led to bureaucratic paralysis, as the two governors frequently clashed over policy, budgets, and jurisdiction.

While mainland China descended into fragmentation during the Warlord Era, Tsz Kong, much like nearby Hong Kong, became a rare enclave of stability. Its dual colonial status ironically made it a neutral ground for political exiles, merchants, and refugees fleeing the chaos. Both the KMT and the CCP sought to establish influence in the city, though British and French authorities carefully suppressed overt political agitation. The colony’s European quarters saw discreet meetings between Chinese revolutionaries and foreign sympathizers—most notably, a small contingent of French communists who traveled to Tsz Kong in the early 1920s to liaise with CCP members. However, their impact was minimal; the British governor, wary of Bolshevik influence, swiftly deported several French radicals, souring relations with Paris.

The Canton-Hong Kong Strike of 1925, a massive worker-led protest against British imperialism, sent ripples into Tsz Kong. While the colony was not a primary target, Chinese dockworkers and rickshaw pullers organized sympathy strikes, briefly paralyzing the port. Unlike in Hong Kong, where protests were met with brutal suppression, Tsz Kong’s dual administration created confusion—British police advocated for harsh crackdowns, while French officials, wary of escalating tensions, hesitated. In the end, the strikes were crushed within weeks, but the incident exposed the fragility of the condominium’s authority. To prevent future unrest, the colonial government imposed stricter controls on labor unions, pushing dissent underground.

The interwar period saw Tsz Kong’s urban core expand dramatically. New neighborhoods sprang up, blending French colonial villas, British-style row houses, and Cantonese tenements, creating a uniquely hybrid architectural landscape. However, beyond the capital, the colony remained vastly underdeveloped. Most of Tsz Kong’s interior was dotted with sleepy market towns, where farmers and fishermen lived much as they had for centuries. The British focused on modernizing the port and military infrastructure, while the French invested in Catholic missions and rubber plantations—neither power saw much value in developing rural Tsz Kong. This neglect would later fuel resentment among the local population, who saw the benefits of colonialism flow only to a privileged few.

With its lax oversight and divided administration, Tsz Kong became a hub for smuggling during the 1920s and 1930s. Opium, firearms, and luxury goods flowed through its poorly monitored docks, often with the tacit approval of corrupt officials. The French side, in particular, gained a reputation for turning a blind eye to arms shipments destined for warlords in Guangdong and Guangxi. Meanwhile, British customs officers focused on intercepting contraband heading into Hong Kong, creating a bizarre cat-and-mouse game between the two colonial factions. This illicit trade enriched a small class of comprador merchants, who operated with near-impunity, further entrenching Tsz Kong’s reputation as a "city of shadows."

By the late 1930s, as Japan’s invasion of China intensified, Tsz Kong’s strategic position made it a potential target. The Anglo-French condominium, already strained by internal disputes, now faced an existential threat. British military planners quietly fortified the colony’s defenses, while the French—distracted by the looming war in Europe—did little to prepare. The local Chinese population, caught between colonial neglect and Japanese aggression, grew increasingly restless. Some began secretly aiding the KMT’s resistance efforts, while others saw the CCP as the only viable alternative to foreign rule. Regardless, a war was coming, and Tsz Kong would absolutely not be spared.

Japanese Occupation (1941-1945)

On December 8th 1941, Tsz Kong was invaded by Japanese forces. Allied forces, consisting of British, French, American, Canadian, Australian and Indian troops defended the city fiercely but it would fall on February 12th 1942, just 3 days before Singapore would fall as well. Having surrendered to the Japanese, all the remaining forces were either imprisoned or executed.

During this time, Tsz Kong suffered greatly, with food being fiercely rationed and the general quality of life dropping. It is estimated that over 530,000 people either died or escaped. A few of those people who escaped would later return as part of the East River (Dongjiang) Column, fighting in the countryside areas of Tsz Kong, much like Hong Kong. The Dongjiang Column would also assist in helping Chinese elites, based in Tsz Kong to escape to nationalist-communist controlled territory.

The territory was handed over back to joint British-French control on August 30th 1945, the same day Hong Kong would be liberated as well. That day, known as Liberation Day, is still celebrated in Tsz Kong to this day and is a public holiday.

Post-War Colonial Era (1945-1971)

In the aftermath of WW2, it was unknown who would control Tsz Kong in the long term. While the Republic of China, under Chiang Kaishek, wanted to gain back all European concessions, including Tsz Kong, the UK and France protested this, arguing that they had been the first to liberate the territory and therefore, had the best claim to Tsz Kong. The US had initially argued in favour of restoring Chinese rule over Tsz Kong, however with the resumption of the Chinese Civil War in 1946, it withdrew its calls for returning Tsz Kong due to the instability. During this time, pro-autonomy sentiments grew among Tsz Kongers, especially those who had been educated overseas pre-war, with some even beginning to call for outright independence if their needs could not be met. While the UK and France would end many of its discriminatory laws in the colony, these sentiments would persist until the end of the colonial period.

Tsz Kong would boom as an industrial hub in the 1950s, with the population growing as a result of refugees escaping to the city after the civil war. Most of the refugees were either Cantonese (specifically Chiuchow) and Fujianese, though there were some Shanghainese and Zhejiangnese who came during this time. Many of these, being intellectuals, would find Tsz Kong to be a preferable home to the mainland, and dreamt of making a free republic. This led the pro-autonomy movement to grow into a full-fledged independence movement by the 1960s, with protests being held regularly demanding it. Initially though, the UK and France were concerned that this would anger China, while also inspiring their remaining colonies to fight for independence. As a result, they tried to suppress this but ultimately failed with American condemnation. They then satisfy the moderates, by allowing for the Legislative Council to become a democratically elected legislature in 1965, though this only emboldened the movement. Many of the existing political parties, who acted more as social organizations rather than proper parties before 1965, would run candidates for the election.

Secretly, the US made a deal with the UK and France in 1966, they could let Tsz Kong go but still have a great deal of influence over it. The UK would accept this, though France was more reluctant and would only accept this 3 years later in 1969. Around the same time, Hong Kong also was inspired by Tsz Kong's independence movement as an independence movement also starting growing there. 4 main parties emerged in Tsz Kong during this time: the Democratic Party: the moderate faction of the pro-independence movement, the Ji Yau Dong: the radical faction of the pro-independence movement, the Workers Party: a socialist party secretly backed by the CCP, and the Labor Party: an independent left-wing party.

Unlike OTL, Henry Kissinger would make his secret trip to China a year earlier in 1970, which would lay the groundwork to better US relations with China. Kissinger persuaded China to give up claims on Hong Kong and Tsz Kong, but that it could get Macau back eventually. Surprisingly, the Chinese authorities agreed to this, and later made a public statement claiming that they would not invade an independent Hong Kong and Tsz Kong should that happen. The same year in May, a referendum was held: to go independent, to stay a colony, or to rejoin China. 63.8% of voters voted for independence as a republic. As a part of the deal, British and French forces would remain in Tsz Kong primarily to help train the new Tsz Kong army, but they would withdraw most of their forces to avoid antagonising China. A constitutional convention was called later that year, involving all the major political figures in the city, to draft a constitution for the republic. While some pushed for a parliamentary republic, with the President being a ceremonial head of state, most pushed for a presidential republic instead, though the parliament was given more powers.

Independence Era (1971-Present Day)

On May 12, 1971, after decades of colonial rule and postwar political maneuvering, Tsz Kong finally gained independence as a sovereign republic. The transition was neither smooth nor entirely peaceful—years of negotiations with Britain and France had been fraught with disputes over military bases, economic concessions, and the rights of European settlers. The country’s first president, Clark Man Tsz Cheung, a charismatic lawyer and leader of the Democratic Party (Min Zhu Dang), took office amidst both celebration and tension. His party had formed an uneasy alliance with the Ji Yau Dong (Freedom Movement), a nationalist group that had long agitated for independence. Together, they narrowly secured power against a fractured opposition that now included the Tong Heung Kuk (United Welfare Association), a conservative, business-aligned faction that had unexpectedly won seats in the first post-independence elections. Though not a traditional political party, the Tong Heung Kuk represented the old elite—colonial-era compradors, industrialists, and even former collaborators with the Japanese occupation—who now sought to maintain influence in the new republic.

The first decade of independence tested Tsz Kong’s fragile democracy. President Man's government faced labor strikes, student protests, and accusations of corruption, while the Tong Heung Kuk used its economic power to undermine reforms. Meanwhile, the Ji Yau Dong, once a key ally, grew disillusioned with the Democratic Party’s compromises and began pushing for more radical land redistribution and anti-colonial rhetoric. The Nationalist Party also rose around this time, arguing for firm anti-communist rhetoric, while also pushing for more autocratic policies. By the mid-1970s, the republic was at a crossroads—would it become a Western-aligned capitalist state like Singapore, or would it embrace more revolutionary rhetoric, aligning itself with China? The answer came through an unexpected force: economic necessity. With few natural resources and a small domestic market, Tsz Kong had no choice but to embrace export-led growth, following the model of its neighbors.

By the late 1970s, Tsz Kong had transformed into one of the "Five Asian Tigers", alongside Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. Its economy boomed thanks to light manufacturing, electronics, and a bustling port sector, while its unique Franco-Cantonese culture became a selling point for tourism. The government invested heavily in education, creating a skilled workforce that attracted foreign investment. Culturally, the 1980s were a golden age—Tsz Kong’s film industry, known for its stylish crime thrillers and romantic melodramas, gained international acclaim, while its Mandopop and Cantopop stars rivalled those of Hong Kong and Taiwan. The capital, Victoria-Sham Uk, became a glittering metropolis of neon-lit streets, French-inspired cafés, and bustling night markets.

With the fall of the communist regime in China in 1989 (which marks the main POD of this timeline aside from Tsz Kong's existence), relations would improve with both Tsz Kong and China, as well as the newly independent Hong Kong which gained its independence in 1995. However, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis hit Tsz Kong hard. As investors fled emerging markets, the republic’s currency plummeted, and property prices collapsed. Unemployment soared, and for the first time in two decades, the economy shrank. The government’s response—a mix of austerity measures and IMF-backed reforms—sparked public outrage. The Tong Heung Kuk, now rebranded as the New Prosperity Alliance, blamed the Democratic Party for mismanagement, while leftist groups accused the elite of protecting their wealth at the expense of the poor. The crisis marked the end of Tsz Kong’s unbridled optimism, forcing a national reckoning with its economic model.

Though the golden age had passed, Tsz Kong’s cultural influence endured. Its films and music remained popular across Asia, and its hybrid Franco-Cantonese identity became a point of national pride. Politically, however, the republic entered a new era of volatility—one where the promises of democracy, prosperity, and equality would be fiercely contested in the decades to come.

Today, Tsz Kong faces a complex array of challenges that test its political stability, economic resilience, and social cohesion. One of the most pressing issues is rising inequality, as the wealth gap between the urban elite and the working class continues to widen, exacerbated by skyrocketing housing prices and stagnating wages. The legacy of its rapid industrialization has also left the country grappling with environmental degradation, including conerns around air pollution and contamination of coastal waters from decades of unregulated manufacturing.

Externally, Tsz Kong faces geopolitical pressures, particularly from China’s increasing regional influence, which has led to tensions over trade, investment, and fears of losing autonomy. Finally, the aging population and declining birthrate threaten long-term economic sustainability, forcing difficult debates over immigration policy and pension reforms. Together, these issues paint a picture of a nation at a crossroads, balancing its storied past with an uncertain future.

Geography

Upon inspection, Tsz Kong appears similar to the Special Administrative Regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau, also located in Southern China. However, Tsz Kong is an independent city-state, more akin to Singapore. Most of the city is located on a peninsula, though there are sveral significant outlying islands.

Districts

The city was reorganised into several districts after independence, replacing the old informal neighbourhoods that had existed since the colonial period, while also formally dividing the different regions which had been used for elections.

| Name | Approx.Population | District Council Seats | |

| 1 | Northwestern | 98,000 | 15 |

| 2 | Lam Wan | 162,000 | 13 |

| 3 | Yeung Liu | 193,000 | 17 |

| 4 | Shek Tung | 214,000 | 15 |

| 5 | Narbonne | 218,000 | 21 |

| 6 | Ngau Hang | 229,000 | 14 |

| 7 | Centrale | 268,000 | 14 |

| 8 | Nam Kong | 298,000 | 12 |

| 9 | Tsim Lok | 345,000 | 22 |

| 10 | Au Tin | 391,000 | 19 |

| 11 | Pak Tong | 435,000 | 16 |

| 12 | Western | 437,000 | 24 |

| 13 | Ap Leng | 465,000 | 16 |

| 14 | Saint Lazare | 467,000 | 21 |

| 15 | Heung Liu | 475,000 | 19 |

| 16 | Ngau Hom | 581,000 | 32 |

| 17 | Siu Hang | 714,000 | 33 |

| 18 | Fa Che | 739,000 | 36 |

| 19 | Blakewood | 798,000 | 38 |

Government

A Parliament and a President are chosen through elections every 3 months.

Most parliament and presidential candidates are members of a political party. The age of the political party has zero bearing on candidate participation.

Parliament members debate bills and discuss issues regarding Tsz Kong, given by the Supervisors of the simulation.

Presidents

| No. | Name | Party | Time in Office |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lieutenant Quattro | Zeonist Party | Jan 3rd 2022-April 25th 2022 (de-facto) |

| 2 | RandomAutobiographyRoamer | Nationalist Party | July 10th 2022-July 16th 2022 (ousted by no confidence vote and emergency election) |

| 3 | Kevinovich | Social Democratic Worker's Party | July 16th 2022-August 16th 2022 |

| 4 | Lieutenant Quattro | Zeonist Party | August 16th 2022-September 5th 2022 (deposed by Jesus) |

| 5 | Citric Acid | Greens | September 8th 2022-October 8th 2022 |

| 6 | Kevinovich | League of Tsz Kong Unity | October 8th 2022-November 8th 2022 |

| 7 | Frogggggg | Tsz Kong Greens (in coalition with Democratic Socialist Alliance) | November 8th 2022-January 19th 2023 |

| 8 | Thoth | Democratic Socialist Greens | January 19th 2023-March 19th 2023 |

| 9 | Zy | Socialist Party of Pixzy | March 19th 2023-April 2nd 2023 (deposed by God) |

| 10 | RandomAutobiographyRoamer | Reformist Nationalist Party | April 4th 2023-October 8th 2023 |

| 11 | Lieutenant Quattro | Marxist Leninist Maoist Party | October 8th 2023-January 4th 2024 |

Current Parties

| Party Name | Party Name (Traditional Chinese/French) | Party Beliefs | Foundation Date (Lore) | Party Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Socialist Greens | Alliance Socialiste Démocratique

民主社會聯盟 |

Democratic Socialism, Pro-democracy, Anti Authoritarianism, and Semi-Presidentialism | 2023,

Democratic Socialist Alliance(1978), The Greens (1995) |

Aqua |

| Reformist Nationalist Party | Parti Nationaliste Reformé

新國民黨 |

Nationalism, State capitalism, Anti-authoritarian communism, Militarism, Right-wing populism, Social conservatism, technocracy | 1996 | RandomAutobiographyRoamer |

| League of Tsz Kong Unity | Ligue de l'unité de Tsz Kong

紫港團結聯盟 |

Centre-Right | 1971 | Sid |

| Marxist Leninist Maoist Party | Parti Maoïste Marxiste-Léniniste

馬主義政黨 |

People's Democracy | 1966 (as Workers Party) | Lieutenant Quattro |

| Gay Party | Parti Gay

同性戀黨 |

Single-Issue Politics, Pro LGBT, Anti Discrimination | 2021 | Keq |

| Alternate for Tsz Kong | Alternative pour Tsz Kong

候補黨 |

Conservativism, Populism, Nationalism, Anti-Socialist/Communist, Integrationism | 2006 | Dusk |

| Solidarity Lane | Voie de Solidarité

團結黨 |

Pro-choice, anti-socialist, pro-secular, center-right, Pro-trade tariffs | 1982 | Ky3653 |

| Justice and Fairness Party | Parti de la justice et de l'équité

正公黨 |

Mainly focuses on promoting policies that are grounded in the principles of justice, public safety, and civil liberties. | 1975 | LazerTC |

| New Democratic Convenant | Nouvelle Alliance Démocratique

新民主盟 |

Centre-Left | 1992 (as NDC), 1965 (as Democratic Party) | Freamy Icy Creamy |

| Federalist Party of the Cantonese Area | Parti fédéraliste de la région Cantonaise

粵區聯邦黨 |

Guangdong-Tsz Kong unity, Cantonese patriotism, interventionism, anti-fascism, anti-communism, federalism, social liberalism | 2014 | Tiandianp |

| Ji Yau Dong | Parti liberté

自由黨 |

Free Market, Centrist Lib-Left, Pro LGBT | 1964 | Idiotroaster |

| The Cardigans | Parti de Cardigans

卡迪黨 |

Anti-Authoritarianism, Anti-Capitalism, Anarchism | 2022 | Stormin |

| Tsz Kong Democratic Party* | Parti démocratique

民主黨 |

Nationalism, Conservatism | 1996 | Bricky |

| Tsz Kong Libright Party | Parti Tsz Kong Libright

自右黨 |

Social Libertarianism, Free Market Economy, Low Taxes | 2001 | kingsnake1 |

| Tsz Kong Yuuist Party | Parti YUU

yuu黨 |

Authoritarianism, economically right/free markets, capitalist, promotes shopping and advertisement/product development | 2016 | Greentea |

| Ocean Party | Parti Océan

海洋黨 |

Libertarian, small businesses, cultural preservation, progressive politics | 1999 | Yosh |

| Youth Party | Parti de des jeunes

青年黨 |

Social Welfare, Social Democracy, Anti-Communism, Anti-Fascism, Third-Way | 2008 | Fork |

| Grasstouching Party | Parti de herbe

草地黨 |

Socialism, Anti-Authoritarianism, Anti-Capitalism | 2016 | June |

| Communist Party of Tsz Kong | Parti Communiste Tsz Kong

紫港共產黨 |

Tsz Kongian Socialism, Communism, Marxism-Leninism, Tsz Kong National Liberation, Peasant-Worker Solidarity, Left- Wing Populism, Pan Socialist Unity, Anti-fascism, Anti-racism. | 1974 | rara_57 |

*Not to be confused the former Democratic Party created in 1966.

Former Parties

| Party Name | Party Name (Traditional Chinese/French) | Party Beliefs | Party Leader |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruffist Party | 獎門黨/Parti Ruffiste | Ruffism | Aqua |

| Tsz Kong Nationalist Party | 紫港國民黨/Parti national de Tsz Kong | Nationalism,Anti communism, State capitalism, Anti-communist, Anti-Marxism, Anti-socialism, Militarism ,Right-wing populism, Social conservatism, technocracy | RandomAutobiographyRoamer |

| Social Democratic Worker's Party | 社會民主黨工人黨/Parti des travailleurs sociaux-démocrates | Social democratic, socialism, left-wing realism, democratic, welfare state, anti-polarisation, anti-populism | Kevinovich |

| Tsz Kong Black Party | Parti Noire de Tsz Kong | Black Supremacy, Black Nationalism, Black Power, Pan-Africanism | hkfemboy |

| Zeonist Party | Parti Zéoniste | Zeonism | Lieutenant Quattro |

| Tsz Kong Greens

(Merged into DSG) |

Les Verts de Tsz Kong

紫港綠黨 |

Green Politics, Progressivism, Anti-Neoliberalism, Left | Citric Acid |

| Labor Party | Parti Travailliste | Social democracy, democratic socialism, liberal conservatism | frogggggg |

| tszkongggag Party | Parti tçékwongggag

TSG黨 |

Nationalism, classical liberalism, social welfare, power to the people. | Ash |

| Monorail Workers Party | Parti des travailleurs du monorail

單軌工人黨 |

Far Left Economically, Centrist Socially | Kedah |

| Britain Forever Party | Parti Grande-Bretagne Toujous | Jesus, patriotism, British accent, British Food, Big Ben | iancyh |

| Tsz Kong Libertarian Party | Parti libertaire Tsz Kong

慈康自由黨 |

Libertarianism, Capitalis | Ronak |

Education

The named schools are listed below, taking in account population and education level (thus referencing Belgium) to around 3200+ schools[1]

| School Name | Associations | Principal | Aim | School Size | School Motto | School Transport | Education Level | Courses | Created by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastline Junior School | Tsz Kong International Schools Foundation (TKISF) | 600 | Joyful Bus 快樂巴士 | Years 1-6 | Primary School | flutters | |||

| Hillside Junior School | 600 | Years 1-6 | Primary School | ||||||

| Turquoise Junior School | 600 | Years 1-6 | Primary School | ||||||

| Horizon School | Ms Joy WONG | To allow students to identify themselves freely and to find themselves. | 1050 | Laetitiam Litterarum | Years 7-13 | MYP, iGCSE, A-Levels, BTEC | |||

| Tsz Kong International School | Ms Winnie POWELL | 1050 | Years 7-13 | MYP, iGCSE, A-Levels | |||||

| South Centrale Ruffist School | Education with ruffist beliefs | frogggggg | |||||||